The Romantic movement came to France much later than it did to England in Germany, and the backlash was correspondingly more severe. The elements of French culture that proved resistant to Romanticism, i.e. the Academie Francaise, and the wide-spread use and popularity of classical form, also proved extremely reactionary, as could be seen on Feb. 25, 1830, when a young Victor Hugo decided to stage a play.

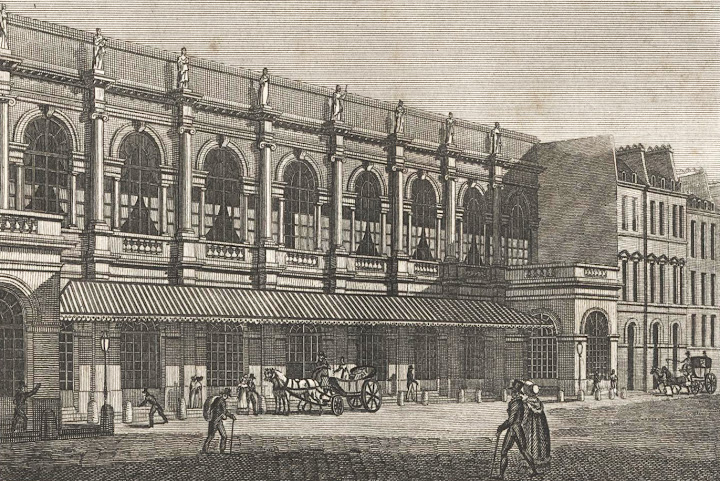

Victor Hugo, who is pretty much The Romantic of the French Romantic movement, broke with tradition when he wrote Hernani, a play that can be summed up as, "Oops, I am in love with someone who is in love with/engaged to someone else and now I have killed myself for no easily discernable reason." Though the main cast was dead in the end, as happens with most French tragedy, Hugo made the great mistake of using forbidden words such as "handkerchief" and forcing the actors to express grand sweeps of Romantic passion while in period costume. One actress was so appalled by her period costume she refused to go onstage without wearing her contemporary but hideous 1830s hat. Since the Comedie Francaise, i.e. the Maison de Moliere, i.e. the oldest theatre company in Europe, i.e. The Be All and End All of French Drama, was deigning to stage a (gasp) Romantic piece, Hugo was understandably nervous about its reception. He therefore passed out red tickets (normally given to the author of any staged drama, like a courtesy copy of a book) to his friends, who formed a Romantic Army and invaded the Comedie Francaise on the opening night.

To make sure the production would begin on time and sans interference from the classicists, the Romantic Army got to the building at three-o-clock and locked themselves in for the next four hours with provisions and their cosplay get-up (Seriously, Hugo himself describes the Romantic Army as full of "wild whimsical characters, bearded, long-haired, dressed in every fashion except the reigning one, in pea-jackets, Spanish cloaks, in waistcoats a la Robespierre, in Henry III bonnets...and this in the middle of Paris in broad daylight"). Sometime before seven-o-clock, they realized that they had no bathrooms, as they had locked themselves into the auditorium, and just did their business in the boxes of the classicists.

The classicists were understandably pissy (in all senses of the word, thanks to the lack of bathrooms) and began having fistfights in the pit. The actors, already unhappy with having to go Romantic and forsake their 1830s habberdashery, were made further unhappy by the fact that they could not get through a single performance without someone in the audience :

a. challenging someone else to a duel,

b. starting a fistfight,

c. hissing at the stage loud enough to drown out the actors,

d. arguing over classical vs. Romantic forms and politics very, very loudly, or

e. getting up onstage in a red waistcoat and lime green pants before the curtain to sing praises of the Romantic, bohemian lifestyle. (Not like that, though. More the songs of angry men.)

Hernani ran for a hundred full-house performances. The Amateur Historian is willing to bet that the actors of the Comedie Francaise hated every one of them.

a. challenging someone else to a duel,

b. starting a fistfight,

c. hissing at the stage loud enough to drown out the actors,

d. arguing over classical vs. Romantic forms and politics very, very loudly, or

e. getting up onstage in a red waistcoat and lime green pants before the curtain to sing praises of the Romantic, bohemian lifestyle. (Not like that, though. More the songs of angry men.)

Hernani ran for a hundred full-house performances. The Amateur Historian is willing to bet that the actors of the Comedie Francaise hated every one of them.