... I ... don't quite know what to say about the movie,

Gothic, so I shall stick with the facts.

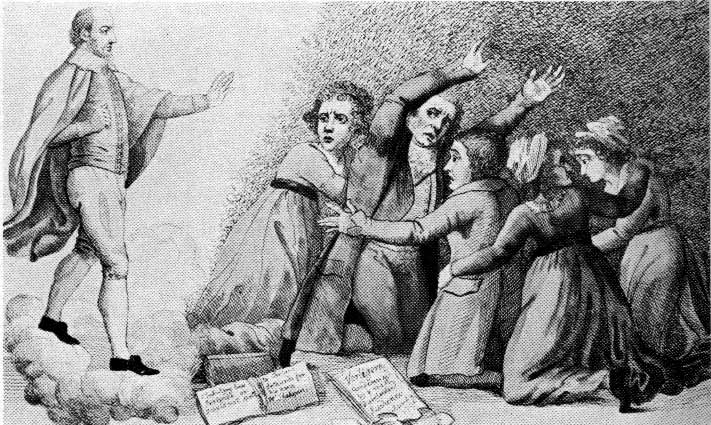

Fact 1: The movie is about the summer of 1816, when Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley), Mary's half-sister Claire Clarmont and Lord Byron's doctor were all living by Lake Geneva. It is, in particular, about the night where they read ghost stories to one another, Byron suggested a ghost story writing competition and Mary Shelley began to write

Frankenstein. Above, you can see an absolutely

adorable Percy Shelley geeking out about Cornelius Agrippa and the metaphysical aspects of lightening, Lord Byron indulgently seducing Per... er, drying Percy Shelley's hair, and Mary Shelley looking freaked out, as she is the

only sane woman amongst a bunch of drunken, extremely high and extremely excitable people.

Fact 2: Percy Shelley is absolutely gorgeous. One (or at least, the Amateur Historian) does not even question the purpose of the nude scene where Percy Shelley attempts to connect with the greater forces of the universe by drinking his weight in laudanum and then climbing onto the roof. One simply looks at Julian Sands's wet, naked body and ceases to question the script.

Fact 3: This movie was made in the 1980s. The soundtrack will remind you of it every five seconds.

Fact 4: The director, like

Blackadder, thinks that a Romantic Poet is someone who wanders around Europe in a poofy shirt trying to get laid. This is certainly true of his Byron, who, alas, crosses from dangerous, sexy rogue into creepy sketchball who seems physically incapable of being in the same room with someone (and, on occasion, something) without at least attempting to seduce them. Odd notion of hospitality, but since his other remarkable acts as a host include trying to stab his doctor, biting Claire Clarmont's neck, and setting his shirt on fire, perhaps one ought to be grateful he only makes the attempt. Perhaps this Byron thinks pick-up lines are part of being polite.

Fact 5: After the first half-hour, resign yourself to the fact that all the main characters are so high they have probably broken through the ozone layer and are contributing to the ecological destruction of our planet, just as surely as the script has brought about the destruction of your willing suspension of disbelief. It is also, apparently, a very bad trip. Claire Clarmont, for example, goes feral and starts catching rats in her teeth.

I Am Not Making This Up.

Fact 6: At certain points, the story is historically accurate. Mary Shelley was inspired by the ghost-story-writing competition, Claire Clarmont

did get pregnant with Lord Byron's illegitimate daughter, Byron was into some kooky and kinky stuff (as in, his half-sister- Gothic goes there and goes there and then takes a month-long, drugg-addled vacation there), Shelley did hear parts of Coleridge's unfinished poem

Christabel and then imagine seeing eyes in the middle of breasts, and Byron's doctor, John Polidori , did hear a vampire story Byron was thinking of writing and then took it, rewrote it to star Byron as a vampire, and then published it to great acclaim. Then, of course, the camera zooms in on a fish in a bird-bath or Byron's incredibly creepy collection of life-sized mechanical dolls and you have no idea what the hell is going on.

Fact 7: Be aware of your own tolerance for horror before renting this film. The Amateur Historian personally thought the creepiest bit of the film, where Mary Shelley goes utterly bonkers, was absolutely hilarious, but the friend sitting next to her had nightmares for a se'enight afterwards.

Fact 8: I don't think I can justify recommending this movie. It is so bizarre I still have difficulty forming an opinion about it. However, if you don't mind a creepy overindulgence in the macabre and drug-addled history, it's two hours of unexpectedly fascinating hilarity.