Ah, spring is here! For those who wish to celebrate in a slightly more unusual way, take these tips from Theophile Gautier:

"It is true that we did not possess Newstead Abbey, with its long, shadowy cloisters, its swans gliding about on the silvery waters in the light of the moon, nor the lovely young sinners,fair, dark, or red-haired, but we could certainly secure a skull, and Gerard de Nerval undertook to do so, his father, a retired army surgeon, having quite a fine anatomical collection.

The skull itself was that of a drum-major, killed at the battle of the Moskowa, and not that of a girl who had died of consumption, so Gerard told us. He further informed us that he had mounted it as a cup by means of a drawer handle fastened by a nut and screw-bolt. The skull was filled with wine, and handed round, each man putting it to his lips with more or less well-concealed repugnance.

"Waiter," cried one of the neophytes, endowed with excessive zeal, "fetch us brine from the ocean!"

"What for, my boy?" asked Jules Vabre.

"Is it not told of Han d'Islande [in Victor Hugo's gothic novel] that 'he drank the briny waters in the skulls of the dead '? Well, I mean to do as he did, and to drink his health. Nothing can be more Romanticist!" "

Or more unsanitary.

Showing posts with label A World of No. Show all posts

Showing posts with label A World of No. Show all posts

Monday, March 12, 2012

Friday, March 2, 2012

Horrible Histories Newgate Prision

Oh capitalism! The amateur Historian feels the urge to quote from Cabaret. "Money makes the world go round, the world go round...."

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Fashion forward!

As spring fashions begin to come out, it's always nice to look to the past to see how the future might turn out. I very much doubt that any of the trousers below will be featured on Chanel or Dior's runways, but I think we can all agree that the field of haberdashery has sadly disappointed the visionaries of 1893 who thought we would be wearing braided cushions as hats in 1965.

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

Maybe this is why she doesn't write to you.

Napoleon and Josephine have one of the more interesting romantic relationships in the Amateur Historian's chosen period. This is partly due to the fact that Napoleon has some really... odd letters. Aside from the famous, perhaps apocryphal note "I am coming-- do not bathe" he rails against Josephine for the strangest reasons.

Take, for example, this... I suppose we ought to call it a love letter:

"I don't love you, not at all; on the contrary, I detest you. You're a naught, gawky, foolish Cinderella.

You never write me; you don't love your own husband; you know what pleasures your letters give him, and yet you haven't written him six lines, dashed off so casually!

What do you do all day, Madam? What is the affair so important as to leave you no time to write to your devoted lover?

What affection stifles and puts to one side the love, the tender constant love you promised him?

Of what sort can be that marvellous being, that new lover that tyrannises over your days, and prevents your giving any attention to your husband?

Josephine, take care! Some fine night, the doors will be broken open and there I'll be.

Indeed, I am very uneasy, my love, at receiving no news of you; write me quickly for pages, pages full of agreeable things which shall fill my heart with the pleasantest feelings.

I hope before long to crush you in my arms and cover you with a million kisses as though beneath the equator.

Napoleon Bonaparte"

After that letter, I'd say the dear Emperor is going to have to wait a long time before crushing Josephine in his arms, even if he does decide that breaking and entering is truly the way into a woman's heart.

Take, for example, this... I suppose we ought to call it a love letter:

"I don't love you, not at all; on the contrary, I detest you. You're a naught, gawky, foolish Cinderella.

You never write me; you don't love your own husband; you know what pleasures your letters give him, and yet you haven't written him six lines, dashed off so casually!

What do you do all day, Madam? What is the affair so important as to leave you no time to write to your devoted lover?

What affection stifles and puts to one side the love, the tender constant love you promised him?

Of what sort can be that marvellous being, that new lover that tyrannises over your days, and prevents your giving any attention to your husband?

Josephine, take care! Some fine night, the doors will be broken open and there I'll be.

Indeed, I am very uneasy, my love, at receiving no news of you; write me quickly for pages, pages full of agreeable things which shall fill my heart with the pleasantest feelings.

I hope before long to crush you in my arms and cover you with a million kisses as though beneath the equator.

Napoleon Bonaparte"

After that letter, I'd say the dear Emperor is going to have to wait a long time before crushing Josephine in his arms, even if he does decide that breaking and entering is truly the way into a woman's heart.

Friday, January 6, 2012

Aargh.

I do not like Twilight

for rather a stupid and specific reason, to be honest. The Amateur Historian

wishes desperately to say that her initial, gut-reaction of dislike arose from

feminist principles, an admiration for the subtleties and satires of Jane

Austen over the sentimentality Brontes, a dislike of melodrama or something of

sort, but it really started because the person who introduced Twilight to the Amateur Historian said

Edward was a "Byronic hero."

Well, no, that’s not quite how it works. The Byronic hero stemmed from the Romantic and

Gothic adulation of Milton’s Paradise

Lost, in particular for his characterization of Satan as a personnage of “flawed grandeur”—a magnificent

and powerful person destroyed through their hamartia, or tragic flaw (hamartia stemming from Aristotle's Ars Poetica).The one to perfect this beloved staple of nineteenth century fiction

was, of course, Lord Byron, who drew from his own self-myth and from the

trajectory of Napoleon, whom Byron saw as a brilliant, dark and mysterious

leader who just also happened to be the author of his own downfall. Byron wrote

these young, oddly charming, prematurely-tainted-by-sin,

trapped-by-the-constraints-of-memory-and-society protagonists in Childe Harold, The Corsair, Lara, and Manfred. Though I suppose Edward does reflect, the

erie, supernatural seducer of Lady Caroline Lamb’s Glenarvon, how is Edward a) a fascinating psychological portrait,

b) lead into his own destruction by free choice and a tragic flaw, or c) representative of

Byron, who, well…

It's enough to make one want to join George Takei's Star Alliance.

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

Oh my, where to begin?

For those Gentle Readers who were unaware, there exists such a thing as Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, which is Exactly What it Says on the Tin. It is literally the text of Pride and Prejudice with new scenes of zombies. Granted, it also includes new scenes of Lady Catherine being a ninja, and the Bennet sisters being well-versed in the martial arts, but after the initial snorts of laughter over the jarring absurity of Jane and Elizabeth Bennet discussing the best method of killing zombie, the real laughs come from Austen's text, not the gruesome, Gothic additions. A lot of the literary devices, which Austen employed with such deftness and elegance, are either forgotten or changed so as not to make much sense.

One could make the arguement that it is very much in the Austen spirit, as it enacts the literary critic Bakhtin's idea of heteroglossia, where the dominant discourse is mocked or subverted, and different types of speech coexist. Here we have the discourse of subtle social commentary and the discourse of B-movie horror films. Amusing, yes, but perhaps not used in the manner that the Marxist Bakhtin would have imagined.

For those who are not Austen purists, it is amusing travel reading, for those who are, it is an abomination. For those who, like the Amateur Historian, like to maintain a critical distance from their reading material, it is not good. The inserted paragraphs are jarring and the characterizations that Austen gives and the new authors give are entirely at odds with each other. The authors seem to recognize this, as at the end of the book, they ask the question if one sees two halves to Elizabeth Bennet's personality, or if it is just sloppy writing. The Amateur Historian is inclined to believe the latter.

Granted, this was the first book the two authors wrote, so it could just be the ordinary faults of a first novel. It is a very creative idea, and a satiric look at the Western literary canon, but one that was somewhat clumsily executed. Though the Amateur Historian really has no intention (or desire) to read Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters it is most likely better put-together.

Is there literary merit to these re-writes? The Amateur Historian thinks not.

Are they fun to read? ... sort of? It depends on what one is looking for, and one's stance on Austen and the sanctity, or not, of the Western canon. It is certainly a clever idea, but Austen's elegant cynicism and her subtle social commentary are quite absent, leaving a sort of illiterate Frankenstein's monster in a bonnet stumbling around a cardboard Hollywood set.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Really Giving Her an Earful

Vincent van Gogh's missing ear is a subject of much amusement and bemusement. According to popular rumor, van Gogh cut off his ear in the city of Arles, in Provence, as a gift to a lady of negotiable affection who did not take an interest in him. The people of Arles- particularly the gendarmerie, the local police force- like to point out that the records show a different story.

the artist Gauguin was paying a visit to M. van Gogh, when the later became extremely violent, threatened to kill Gauguin and accidentally cut off his own ear. Gaughin left Arles, and M. van Gogh, in his drunken state, decided that the best thing to do was to wander outside, give his ear to the first prostitute he saw in a nearby brothel, then pass out in his own blood in his room.

It is little wonder why the people of Arles only really liked M. van Gogh once he left them.

Labels:

A World of No,

Arles,

France,

Impressionism,

Vincent van Gogh

Thursday, December 10, 2009

Silly Novels by Silly Lady Novelists

On the subject of scathing reviews, George Elliot, though not as vitriolic about one novel in particular, released her considerable hatred of silly novels in the absolutely brilliant essay "Silly Novels by Silly Lady Novelists". Though the Amateur Historian is not entirely sure if it was intended to do so, the essay also reads like a very good argument for female education. Educate ladies or they, in turn; will write incredibly stupid novels and give all female novelists a bad name.

The Amateur Historian almost wishes to copy-paste the entire thing, but have a few gems before going off to read this masterpiece yourself:

-The heroine's eyes and her wit are both dazzling; her nose and her morals are alike free from any tendency to irregularity.

-The men play a very subordinate part by her side. You are consoled now and then by a hint that they have affairs, which keeps you in mind that the working-day business of the world is somehow being carried on, but ostensibly the final cause of their existence is that they may accompany the heroine on her 'starring' expedition through life.

-The fair writers have evidently never talked to a tradesman except from a carriage window; they have no notion of the working-classes except as 'dependents'; they think five hundred a-year a miserable pittance; Belgravia and 'baronial halls' are their primary truths; and they have no idea of feeling interest in any man who is not at least a great landed proprietor, if not a prime minister. [Watch out Pitt the Younger!] It is clear that they write in elegant boudoirs, with violet-coloured ink and a ruby pen; that they must be entirely indifferent to publishers' accounts, and inexperienced in every form of poverty except poverty of brains.

-Their intellect seems to have the peculiar impartiality of reproducing both what they have seen and heard, and what they have not seen and heard, with equal unfaithfulness.

- We are not surprised to learn that the mother of this infant phenomenon, who exhibits symptoms so alarmingly like those of adolescence repressed by gin, is herself a phoenix... she can talk with perfect correctness in any language except English.

-This enthusiastic young lady, by dint of reading the newspaper to her father, falls in love with the prime minister, who, through the medium of leading articles and "the resumé of the debates," shines upon her imagination as a bright particular star, which has no parallax for her.... Perhaps the words "prime minister" suggest to you a wrinkled or obese sexagenarian; but pray dismiss the image. Lord Rupert Conway has been "called while still almost a youth to the first situation which a subject can hold in the universe," and even leading articles and a resumé of the debates have not conjured up a dream that surpasses the fact. [Either someone has fangirled William Pitt the Younger to an alarming extent and thus either 'forgot' that his emotional life more-or-less stopped developing as soon as he entered office and ignored the fact that he was more-or-less asexual, or they have decided that just any old 24-year-old can be Prime Minister without having a successful Prime Minister for a father, a genius for mathematics and economics, a childhood education structured around the goal of becoming Prime Minister or the extraordinary set of personality-driven power-struggles plaguing the House of Commons that paved Pitt's way to power.]

-(a quote from a novel): "Was this reality?"

Very little like it, certainly.

-He is not only a romantic poet, but a hardened rake and a cynical wit; yet his deep passion for Lady Umfraville has so impoverished his epigrammatic talent, that he cuts an extremely poor figure in conversation. When she rejects him, he rushes into the shrubbery, and rolls himself in the dirt.

-To judge from their writings, there are certain ladies who think that an amazing ignorance, both of science and of life, is the best possible qualification for forming an opinion on the knottiest moral and speculative questions. Apparently, their recipe for solving all such difficulties is something like this:–Take a woman's head, stuff it with a smattering of philosophy and literature chopped small, and with false notions of society baked hard, let it hang over a desk a few hours every day, and serve up hot in feeble English, when not required.

-In such cases, sons are often sulky or fiery, mothers are alternately manoeuvring and waspish, and the portionless young lady often lies awake at night and cries a good deal. We are getting used to these things now, just as we are used to eclipses of the moon, which no longer set us howling and beating tin kettles.

-A recent example of this heavy imbecility is, "Adonijah, a Tale of the Jewish Dispersion," which forms part of a series, "uniting," we are told, "taste, humour, and sound principles." "Adonijah," we presume, exemplifies the tale of "sound principles;" the taste and humour are to be found in other members of the series.

You can read the rest of Eliot's essay here.

The Amateur Historian almost wishes to copy-paste the entire thing, but have a few gems before going off to read this masterpiece yourself:

-The heroine's eyes and her wit are both dazzling; her nose and her morals are alike free from any tendency to irregularity.

-The men play a very subordinate part by her side. You are consoled now and then by a hint that they have affairs, which keeps you in mind that the working-day business of the world is somehow being carried on, but ostensibly the final cause of their existence is that they may accompany the heroine on her 'starring' expedition through life.

-The fair writers have evidently never talked to a tradesman except from a carriage window; they have no notion of the working-classes except as 'dependents'; they think five hundred a-year a miserable pittance; Belgravia and 'baronial halls' are their primary truths; and they have no idea of feeling interest in any man who is not at least a great landed proprietor, if not a prime minister. [Watch out Pitt the Younger!] It is clear that they write in elegant boudoirs, with violet-coloured ink and a ruby pen; that they must be entirely indifferent to publishers' accounts, and inexperienced in every form of poverty except poverty of brains.

-Their intellect seems to have the peculiar impartiality of reproducing both what they have seen and heard, and what they have not seen and heard, with equal unfaithfulness.

- We are not surprised to learn that the mother of this infant phenomenon, who exhibits symptoms so alarmingly like those of adolescence repressed by gin, is herself a phoenix... she can talk with perfect correctness in any language except English.

-This enthusiastic young lady, by dint of reading the newspaper to her father, falls in love with the prime minister, who, through the medium of leading articles and "the resumé of the debates," shines upon her imagination as a bright particular star, which has no parallax for her.... Perhaps the words "prime minister" suggest to you a wrinkled or obese sexagenarian; but pray dismiss the image. Lord Rupert Conway has been "called while still almost a youth to the first situation which a subject can hold in the universe," and even leading articles and a resumé of the debates have not conjured up a dream that surpasses the fact. [Either someone has fangirled William Pitt the Younger to an alarming extent and thus either 'forgot' that his emotional life more-or-less stopped developing as soon as he entered office and ignored the fact that he was more-or-less asexual, or they have decided that just any old 24-year-old can be Prime Minister without having a successful Prime Minister for a father, a genius for mathematics and economics, a childhood education structured around the goal of becoming Prime Minister or the extraordinary set of personality-driven power-struggles plaguing the House of Commons that paved Pitt's way to power.]

-(a quote from a novel): "Was this reality?"

Very little like it, certainly.

-He is not only a romantic poet, but a hardened rake and a cynical wit; yet his deep passion for Lady Umfraville has so impoverished his epigrammatic talent, that he cuts an extremely poor figure in conversation. When she rejects him, he rushes into the shrubbery, and rolls himself in the dirt.

-To judge from their writings, there are certain ladies who think that an amazing ignorance, both of science and of life, is the best possible qualification for forming an opinion on the knottiest moral and speculative questions. Apparently, their recipe for solving all such difficulties is something like this:–Take a woman's head, stuff it with a smattering of philosophy and literature chopped small, and with false notions of society baked hard, let it hang over a desk a few hours every day, and serve up hot in feeble English, when not required.

-In such cases, sons are often sulky or fiery, mothers are alternately manoeuvring and waspish, and the portionless young lady often lies awake at night and cries a good deal. We are getting used to these things now, just as we are used to eclipses of the moon, which no longer set us howling and beating tin kettles.

-A recent example of this heavy imbecility is, "Adonijah, a Tale of the Jewish Dispersion," which forms part of a series, "uniting," we are told, "taste, humour, and sound principles." "Adonijah," we presume, exemplifies the tale of "sound principles;" the taste and humour are to be found in other members of the series.

You can read the rest of Eliot's essay here.

Thursday, December 3, 2009

On the subject of Napoleon and letters, the first year of his Italian Campaign produced some absolute doozies of love letters to Josephine, who was extremely turned off by Napoleon's phonetic spelling, dreadful grammar, abysmal diction and horrible habit of underlining erotic passages so violently that he occasionally scratched through the stationary.

She was therefore extremely disinclined to write back to Napoleon and even less inclined to write to him as he wished her to, i.e. "Make sure you tell me that you are convinced you love me beyond what it is possible to imagine."

Napoleon eventually went somewhat mad at the lack of response, to the point where the Directory began to worry that the Republic's best and most successful general might actually quit his post, abandon Italy and march on Paris. Barras personally sent Josephine to Italy, which at least saved Josephine the indignity of having to answer letters begging her not to bathe.

Labels:

A World of No,

Barras,

Directory,

Josephine,

Napoleon

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

The Style Napoleon III

The Amateur Historian is not a fan of the Opera Garnier, which, in the Amateur Historian's humble opinion, looks as if the Baroque Era ate a bit of Romanticism that disagreed with it, then puked it up in the form of a building, then got so ashamed of what it had done, it kept flinging gold leaf, drapes, tassels, mirrors, tapestries and paintings at its mess. The Empress Eugenie, the wife of Emperor Napoleon III, during whose reign the Opera Garnier was first commissioned, did not like the building either.

When Garnier first submitted the designs for the Opera, the Empress looked at the bizarre Versailles-gone-so-froo-froo-wild-on-a-gold-leaf-bender plan and demanded what the building's style was supposed to be.

Garnier, looking at the Emperor, replied, "The style Napoleon III."

Needless to say, his design won.

Friday, June 19, 2009

Erickson's "historical entertainment": Neither Historical Nor Entertaining

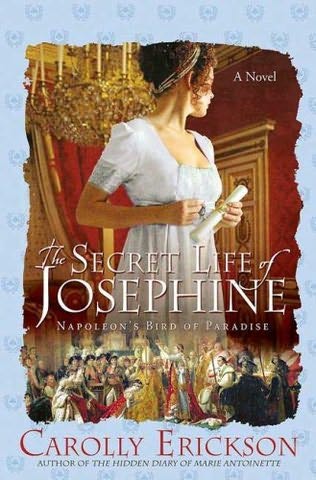

The Amateur Historian picked up a novel entitled The Secret Life of Josephine: Napoleon's Bird of Paradise from her local library, which was just the beginning of her intellectual torture.

The Amateur Historian picked up a novel entitled The Secret Life of Josephine: Napoleon's Bird of Paradise from her local library, which was just the beginning of her intellectual torture."Hunh," said the Amateur Historian to herself. "The author seems familiar. Maybe I've liked her previous stuff? I'll check it out."

Unfortunately, the Amateur Historian was familiar with the author because she wrote, without doubt, the worst book I have ever read, the godawful excuse for a novel, The Hidden Diary of Marie Antoinette, which, upon reflection, deserves every nasty thing the Amateur Historian is insinutating.

Truth is, according to Kierkegaard, subjective, so someone may find redeeming features in The Hidden Diary of Marie Antoinette. The Amateur Historian does not. Erickson prides herself on writing something called, "historical entertainment", which is neither historical nor entertaining. In these sad excuses for works of even dubious literary merit, Carolly Erickson picks a famous female historical figure, preferably one with a crown, and invents a really boring and simplistic world in which a simplified-to-the-point-of-inanity version of said historical figure makes the readers wish for the protagonist's painful demise with every page.

The Amateur Historian is a huge fan of the Empress Josephine and has read some marvelous historical fantasies about Josephine wherein the author actually does research, effectively simplifies the historical event to narrative form while keeping most of its complexity and presents a sympathetic but flawed character whose motives are understandable and who seems a genuine part of their society. Those books were the Josephine B trilogy by the marvelous Sandra Gulland.

It was not this wretched excuse for fiction by Erickson, which ought to have been named Josephine's Dear Penthouse Letter: A Bizarre Metaphor That Does Not Even Appear in the Text.

This book, though I hesitate to call it a book since it failed so much at being part of any genre but that of Gross Stupidity, has little to no relationship with historical fact, except that it appears Erickson once-upon-a-time read a general life-and-times biography of Josephine and decided that the characters were too complex and the time period too interesting and, furthermore, that the mentions of Josephine's love affairs weren't explicit and annoying enough.

Thus, this travesty of a novel was vomited forth into hardback.

I cannot begin to say how truly awful this book was. I hated it. I hated every historical inaccuracy, I hated every character Erickson introduced and I hated the fact that an intelligent, politically astute, clever woman was reduced to Miss Look-Who-I-Slept-With (which is apparently most of Europe). There was so much more to Josephine than the fact that she had sex! Unfortunately, Erickson either doesn't believe so, or feels that a complex emotional, spiritual and/or intellectual inner life makes for boring reading. Ditto with historical fact. Who cares how Napoleon's Grande Armee, the largest military force Europe had ever seen, met with disaster in Russia if there isn't sex involved?

And then, there is her godawful Napoleon. This is a man who is still revered as a hero, who inspired the poorest, worst-supplied army in Europe to capture Italy from the supposedly unbeatable Austrian forces, who created an entire legal system, who seized control of France when he was only thirty and whose army was so devoted they turned on Louis XVIII to support Napoleon at Waterloo. You'd be surprised by that if your only knowledge of the Napoleonic era came from this awful excuse for historical fiction. Napoleon is truly hateful and amazingly stupid. Though he hates Josephine (this from a man who, according to his generals, worshiped his wife, and whose existing letters to her are embarrassingly explicit) and grows to loathe her over the course of the novel, he bows to her every whim. God alone knows why, since this Josephine was one of the most unappealing characters I've had the misfortune to read. She is flat, one-dimensional, boring, and so annoying I still had no sympathy for her aafter the author attempted to force the readers to like Josephine by having someone rape the future Empress (which is just one of many "what the hell?" moments for anyone with a passing acquaintance with the historical time period or personnages).

I would like to give this novel a negative grade for not only failing to be even accidentally historically accurate, but also failing to have any of the conventional traits of fiction, like, well-rounded, interesting characters, a compelling plot, useful dialogue, wit, intelligence or proof of the author's basic literacy. What was the point of writing a prologue displaying that she had, in fact, done research, when absolutely none of it made it into the book?

Thus, this travesty of a novel was vomited forth into hardback.

I cannot begin to say how truly awful this book was. I hated it. I hated every historical inaccuracy, I hated every character Erickson introduced and I hated the fact that an intelligent, politically astute, clever woman was reduced to Miss Look-Who-I-Slept-With (which is apparently most of Europe). There was so much more to Josephine than the fact that she had sex! Unfortunately, Erickson either doesn't believe so, or feels that a complex emotional, spiritual and/or intellectual inner life makes for boring reading. Ditto with historical fact. Who cares how Napoleon's Grande Armee, the largest military force Europe had ever seen, met with disaster in Russia if there isn't sex involved?

And then, there is her godawful Napoleon. This is a man who is still revered as a hero, who inspired the poorest, worst-supplied army in Europe to capture Italy from the supposedly unbeatable Austrian forces, who created an entire legal system, who seized control of France when he was only thirty and whose army was so devoted they turned on Louis XVIII to support Napoleon at Waterloo. You'd be surprised by that if your only knowledge of the Napoleonic era came from this awful excuse for historical fiction. Napoleon is truly hateful and amazingly stupid. Though he hates Josephine (this from a man who, according to his generals, worshiped his wife, and whose existing letters to her are embarrassingly explicit) and grows to loathe her over the course of the novel, he bows to her every whim. God alone knows why, since this Josephine was one of the most unappealing characters I've had the misfortune to read. She is flat, one-dimensional, boring, and so annoying I still had no sympathy for her aafter the author attempted to force the readers to like Josephine by having someone rape the future Empress (which is just one of many "what the hell?" moments for anyone with a passing acquaintance with the historical time period or personnages).

I would like to give this novel a negative grade for not only failing to be even accidentally historically accurate, but also failing to have any of the conventional traits of fiction, like, well-rounded, interesting characters, a compelling plot, useful dialogue, wit, intelligence or proof of the author's basic literacy. What was the point of writing a prologue displaying that she had, in fact, done research, when absolutely none of it made it into the book?

There is nothing redeeming about this novel. If you can find it, Gentle Readers, pray inform me. I gave up when Josephine decided to travel to Russia after Napoleon.

... on second thought, that would mean forcing my Gentle Readers to expose themselves to such radioactive garbage. Forget the existance of this book. It will be better for everyone involved. I am personally attempting to find brain bleach to forget I ever wasted my time on something so hopelessly bad.

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Why on p. 47, I lost all respect for the author.

The field of biography is a tricky one, fraught with many perils, the chief of which is falling in love with your subject. The other is coming off as an absolute idiot, either by failing to explain what was going on, by explaining too much, or by explaining in such a fashion as to make your readers doubt your sanity, your literacy, or your mastery of contemporary English.

I am sorry to say that this passage, from Eric Metaxas's Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery fulfils almost all of them. Since I fear, Gentle Readers, that you will not have any idea of Mr. Metaxas's subject based on what he wrote, allow the Amateur Historian to explain that Mr. Metaxas is describing a carriage ride in the Alps taken by William Wilberforce, he of the great mind and moral character, but diminutive stature, and Isaac Milner, an intellectual and physical giant elected to the Royal Society as an undergraduate at Cambridge. This is copied verbatim.

"The extraordinary felicity of this scene, of these incandescent minds meeting on this subject of eternal things, sailing in their horse-drawn coach through the mountains, seems like something out of a fairy tale, one in which a gnome and a giant on a journey in a sphere of glass and silver discover the Well at the World's End, and drinking a draught therefrom learn the secret meaning at the heart of the universe."

... a gnome? That's just mean.

Monday, May 18, 2009

Gothic

... I ... don't quite know what to say about the movie, Gothic, so I shall stick with the facts.

Fact 1: The movie is about the summer of 1816, when Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley), Mary's half-sister Claire Clarmont and Lord Byron's doctor were all living by Lake Geneva. It is, in particular, about the night where they read ghost stories to one another, Byron suggested a ghost story writing competition and Mary Shelley began to write Frankenstein. Above, you can see an absolutely adorable Percy Shelley geeking out about Cornelius Agrippa and the metaphysical aspects of lightening, Lord Byron indulgently seducing Per... er, drying Percy Shelley's hair, and Mary Shelley looking freaked out, as she is the only sane woman amongst a bunch of drunken, extremely high and extremely excitable people.

Fact 2: Percy Shelley is absolutely gorgeous. One (or at least, the Amateur Historian) does not even question the purpose of the nude scene where Percy Shelley attempts to connect with the greater forces of the universe by drinking his weight in laudanum and then climbing onto the roof. One simply looks at Julian Sands's wet, naked body and ceases to question the script.

Fact 3: This movie was made in the 1980s. The soundtrack will remind you of it every five seconds.

Fact 4: The director, like Blackadder, thinks that a Romantic Poet is someone who wanders around Europe in a poofy shirt trying to get laid. This is certainly true of his Byron, who, alas, crosses from dangerous, sexy rogue into creepy sketchball who seems physically incapable of being in the same room with someone (and, on occasion, something) without at least attempting to seduce them. Odd notion of hospitality, but since his other remarkable acts as a host include trying to stab his doctor, biting Claire Clarmont's neck, and setting his shirt on fire, perhaps one ought to be grateful he only makes the attempt. Perhaps this Byron thinks pick-up lines are part of being polite.

Fact 5: After the first half-hour, resign yourself to the fact that all the main characters are so high they have probably broken through the ozone layer and are contributing to the ecological destruction of our planet, just as surely as the script has brought about the destruction of your willing suspension of disbelief. It is also, apparently, a very bad trip. Claire Clarmont, for example, goes feral and starts catching rats in her teeth. I Am Not Making This Up.

Fact 6: At certain points, the story is historically accurate. Mary Shelley was inspired by the ghost-story-writing competition, Claire Clarmont did get pregnant with Lord Byron's illegitimate daughter, Byron was into some kooky and kinky stuff (as in, his half-sister- Gothic goes there and goes there and then takes a month-long, drugg-addled vacation there), Shelley did hear parts of Coleridge's unfinished poem Christabel and then imagine seeing eyes in the middle of breasts, and Byron's doctor, John Polidori , did hear a vampire story Byron was thinking of writing and then took it, rewrote it to star Byron as a vampire, and then published it to great acclaim. Then, of course, the camera zooms in on a fish in a bird-bath or Byron's incredibly creepy collection of life-sized mechanical dolls and you have no idea what the hell is going on.

Fact 7: Be aware of your own tolerance for horror before renting this film. The Amateur Historian personally thought the creepiest bit of the film, where Mary Shelley goes utterly bonkers, was absolutely hilarious, but the friend sitting next to her had nightmares for a se'enight afterwards.

Fact 8: I don't think I can justify recommending this movie. It is so bizarre I still have difficulty forming an opinion about it. However, if you don't mind a creepy overindulgence in the macabre and drug-addled history, it's two hours of unexpectedly fascinating hilarity.

Labels:

A World of No,

Byron,

Film Reviews,

Mary Shelley,

Shelley

Sunday, May 3, 2009

Another Bad Choice in Publishing from the Shelley Family

Comparatively recently (as in the 1950s), scholars found an unpublished novella by Mary Godwin Shelley, author of the generally grossly misinterpreted novel Frankenstein. This novel was in a similar Gothic vien and is called Mathilda.

It is... strange, to say the least. Like many early novels, Mathilda is semi-autobiographical. Mary Shelley's mother, the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, died shortly after Mary Shelley's birth; Mathilda's mother does as well. Mary Shelley grew up in comparative seculsion in Scotland; so does Mathilda. When Mary Shelley's father, William Godwin, fetched her from Scotland to bring her to London, he remarked on the remarkable similiaries in face and form between Mary Shelley and her mother.

However, Mathilda's father returns for his daughter (Mathilda's father, who never gets a name, has been wandering around Europe for no easily discernable reason other than narrative convenience), remarks several times on her similarities to her mother, and sweeps her off to London where he promptly falls in love with her.

... yes, you read that correctly, gentle reader. Mathilda is, in fact, about incest. Incest was a popular subject with the second generation English Romantics. Byron's heroes, when not homoerotically tangled in a "last embrace of foes" that exceeds in passion any between a man and a woman (read The Giacour for more details), tend to be in love with someone morally and ethically unsuitable. This someone often turns out to be the hero's sister.

Mary Shelley sent this manuscript to her father, William Godwin, a successful publisher. The Amateur Historian assumes that Mary Shelley had thought that the novel would sell as well as Frankenstein had, considering that it was both extremely creepy and tragic and concerned a popular trope, i.e. incest. Her father was a well-known publisher; surely he would be able to print it?

Wisely, William Godwin decided not to publish it, lest London society thought him in love with his daughter.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)