Showing posts with label Book Reviews. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Book Reviews. Show all posts

Saturday, April 7, 2012

The History of a Young Lady's Various Fits of Tears

Fanny Burney's Evelina is the novel that shot the author to fame, fortune, inclusion to all the best salons and membership to perhaps the most entertainingly named group of the late eighteenth century, 'the Witlings'. I therefore entered into the novel with only the minor qualm that I am not fond of epistolary novels.

When I finished the book and my kindle kindly asked me to rate the book, all I could think was, 'Meh.'

That is not to say the book was entirely without merit. There are sparkling parts of the text-- Burney is not as deft a hand at satire as Jane Austen, but she still does it remarkably well and she forms very entertaining and likeable characters, as long as they are not her hero and heroine. I had the same problem with the loving couple at the center of Evelina as with the lachremouse lovers Mrs. Radcliffe so unkindly inflicted on her readers in The Mysteries of Udolpho: the lady spent at least a third of the book crying, being silent or otherwise not speaking, displaying her personality or proving her worth as a human being, and the gentleman never actually seemed like a believable human being. I dislike the romances about equally: in Evelina, there heroine is so shy, quiet, awkward and embarrassed with most of her interactions with the hero that I simply couldn't believe that the hero could possibly form even a friendship with her, as he did, let alone a favorable impression of her and later a lasting devotion. Why should he? All she does is be embarrassed and uncomfortable around him. If it was an Austen novel, instead of a Burney one, I would be inclined to say that Evelina and her exemplary Lord Orville will soon get very bored with each other and have a very unhappy marriage. However, it is Burney, so Evelina will live on in silent, agitated, often tearful happiness to write long letters with perfect recall of hours-long conversations.

However, unlike The Mysteries of Udolpho, I hated the hero because he was Lord Honorable McBlandyPants and had no interesting flaws, foibles or indeed any part of his character that was not boringly perfect. The heroine was a little better than the weeping Emily; Evelina likewise resembles an ambulatory fountain that random gentlemen kept wanting to molest, but she makes a number of mistakes out of ignorance and then endeavors to correct them. She, at least, has a functioning brain.

The Amateur Historian did not feel the same antipathy she did towards The Mysteries of Udolpho, but, though I liked the satire quite a lot, and enjoyed the taste of late eighteenth century dialects, the heroine-narrator has the unfortunate tendency to sentimentalize and moralize over everyone she meets (except the hero who is always, and ever, a paragon of tedium and virtue). I, as a reader, prefer to draw my own conclusions and not have the author present to me what I ought to think. However, this is Burney's first novel, so I will not write her off entirely. Perhaps (after a judicious dose of Voltaire or Austen), I shall try Fanny Burney again.

Next time, one hopes to find a less soggy heroine.

Sunday, February 27, 2011

The Beau Brummel Mystery Series!

Gentle Readers, my sincerest apologies for a long and unexplained absence! The Amateur Historian, though being but a modest student of history, is in reality a full-time student at university writing an honors thesis. Since that is (mostly) finished, I hereby swear that your Amateur Historian will again be purveying amusing historical anecdotes.

And book reviews!

The Amateur Historian, as it must be admitted, has a soft spot for dandies, and Beau Brummel is certainly the One Dandy to Rule Them All. So, when she spotted a mystery series about said gentleman, she immediately checked out several books at once. The text itself is... mostly successful. Sort of.

It is extremely clear that the Beau Brummell mystery series by Rosemary Stevens is painstakingly and wonderfully researched, but the Amateur Historian has to question both the detective ability of a man who took four hours to get dressed every morning, and the author's addiction to descriptive clause openings for sentences. If you will forgive the momentary pastiche, a paragraph reads something like: "Wearing a black bombazine dress with a high- waist and a black lace mantilla, she came towards me. Thinking quickly, I deduced it was because no one of fashion wears bombazine unless they were in mourning. As I am known as the arbitrator of fashion, she should have known better- how could she have known her rich uncle had been foully murdered when I had out-ridden the messenger come from London? Smirking, I lifted my quizzing glass...." and so on and so forth until there's slightly awkward dialogue.

The problem with having really clever characters- or using historical personages that are well known for their bon mots and on-dits and scathing wit- is that they actually have to sound clever when they're speaking. If one is not particularly clever at turning a phrase in Austen-style language, or coming up with a subtle yet scathing insult without tumbling into cringe-inducing territory, one had best get a really cracking editor. Beau Brummel was known as much as for what he said as for what he wore. There is also the matter of Brummell's love life. Though one would have certain... associations, shall we say, with basically the Regency equivalent of a male model, Brummell is staunchly heterosexual and, oh joy of joys, also receives a Mary Sue as his potential love interest, as well as (for some reason) the Duchess of York. You know, the one who was so ugly all the newspapers praised her small feet, leading Gillray to create this print?

She's apparently prettier than the Duchess of Devonshire.

Yeah.

On the other hand, the plotting of the mystery is excellent and the murders are always extremely interesting. They read like plots Agatha Christy might have come up with if she was writing about Regency Britain.

The Beau Brummel mystery series has the distinction of being better plotted than another series of novels solved by real life historical figures of the Regency Era, i.e. the Jane Austen mystery series. Neither of them has the distinction of having main characters as witty as their real life counterparts. The Amateur Historian's advice on the disappointing repartee in both?

If you are going to have someone famous for their wit as your main character, you have to make them witty. This is one case where shameless plagerism of someone else's aphorisms and quips is a really good idea.

And book reviews!

The Amateur Historian, as it must be admitted, has a soft spot for dandies, and Beau Brummel is certainly the One Dandy to Rule Them All. So, when she spotted a mystery series about said gentleman, she immediately checked out several books at once. The text itself is... mostly successful. Sort of.

It is extremely clear that the Beau Brummell mystery series by Rosemary Stevens is painstakingly and wonderfully researched, but the Amateur Historian has to question both the detective ability of a man who took four hours to get dressed every morning, and the author's addiction to descriptive clause openings for sentences. If you will forgive the momentary pastiche, a paragraph reads something like: "Wearing a black bombazine dress with a high- waist and a black lace mantilla, she came towards me. Thinking quickly, I deduced it was because no one of fashion wears bombazine unless they were in mourning. As I am known as the arbitrator of fashion, she should have known better- how could she have known her rich uncle had been foully murdered when I had out-ridden the messenger come from London? Smirking, I lifted my quizzing glass...." and so on and so forth until there's slightly awkward dialogue.

The problem with having really clever characters- or using historical personages that are well known for their bon mots and on-dits and scathing wit- is that they actually have to sound clever when they're speaking. If one is not particularly clever at turning a phrase in Austen-style language, or coming up with a subtle yet scathing insult without tumbling into cringe-inducing territory, one had best get a really cracking editor. Beau Brummel was known as much as for what he said as for what he wore. There is also the matter of Brummell's love life. Though one would have certain... associations, shall we say, with basically the Regency equivalent of a male model, Brummell is staunchly heterosexual and, oh joy of joys, also receives a Mary Sue as his potential love interest, as well as (for some reason) the Duchess of York. You know, the one who was so ugly all the newspapers praised her small feet, leading Gillray to create this print?

She's apparently prettier than the Duchess of Devonshire.

Yeah.

On the other hand, the plotting of the mystery is excellent and the murders are always extremely interesting. They read like plots Agatha Christy might have come up with if she was writing about Regency Britain.

The Beau Brummel mystery series has the distinction of being better plotted than another series of novels solved by real life historical figures of the Regency Era, i.e. the Jane Austen mystery series. Neither of them has the distinction of having main characters as witty as their real life counterparts. The Amateur Historian's advice on the disappointing repartee in both?

If you are going to have someone famous for their wit as your main character, you have to make them witty. This is one case where shameless plagerism of someone else's aphorisms and quips is a really good idea.

Labels:

Beau Brummel,

Book Reviews,

Gillray,

Jane Austen,

mystery

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Napoleon's Novel

In 1795, Napoleon wrote a novel. Why yes, gentle reader, you did read that correctly. It is not a very good novel, though it has a somewhat startling predictive value for any scholar of Napoleon's life.

Clisson and Eugenie is the name of Napoleon's masterwork, a nine-page (count 'em!) romance with an extremely awkward writing style, endearing earnestness and a very cliched plot. Clisson, our hero, is a humor-less twenty-year-old who "understood nothing of word play" and "whose power, sangfroid, courage and moral firmness only increased the number of his enemies". Isn't he a charmer?

Clisson meets two sisters and falls in love with the younger one, Eugeine (which happened to Napoleon right before he took up his pen; he and his brother Joseph met the sixteen-year-old Desiree Clary and her sister, Julie, in 1794. Joseph married Julie, after Napoleon steered him away from Desiree who- guess what!- he nicknamed Eugenie).

Clisson then apparently forgets that there's a war going on, marries Eugeine and starts producing an alarming number of sons within the span of six years. Napoleon then, somewhat unnecessarily, points out that his hero and heroine "remain lovers". Clisson, however, gets appointed a commander of the army and manages to win a string of victories that surpasses "the hopes of the people and the army". However, the victories come at a price and Clisson is wounded. He sends his "loyal" aide-de-camp to tell his wife the news and, expectedly, the aide-de-camp seduces Eugeine (no one is really sure why) and Clisson decides to die. After bitterly and passive-agressively demanding that Eugenie "live contentedly without ever thinking of the unhappy Clisson" and that his sons "may not have the ardent soul of their father, lest they be victims of men, of glory and of love". Clisson then gets "pierced by a thousand blows" (ouch) and dies. The End.

Whatever your personal feelings on Napoleon's epic military career, I think we can all agree that it's good thing that his literary career came to an end.

Clisson and Eugenie is the name of Napoleon's masterwork, a nine-page (count 'em!) romance with an extremely awkward writing style, endearing earnestness and a very cliched plot. Clisson, our hero, is a humor-less twenty-year-old who "understood nothing of word play" and "whose power, sangfroid, courage and moral firmness only increased the number of his enemies". Isn't he a charmer?

Clisson meets two sisters and falls in love with the younger one, Eugeine (which happened to Napoleon right before he took up his pen; he and his brother Joseph met the sixteen-year-old Desiree Clary and her sister, Julie, in 1794. Joseph married Julie, after Napoleon steered him away from Desiree who- guess what!- he nicknamed Eugenie).

Clisson then apparently forgets that there's a war going on, marries Eugeine and starts producing an alarming number of sons within the span of six years. Napoleon then, somewhat unnecessarily, points out that his hero and heroine "remain lovers". Clisson, however, gets appointed a commander of the army and manages to win a string of victories that surpasses "the hopes of the people and the army". However, the victories come at a price and Clisson is wounded. He sends his "loyal" aide-de-camp to tell his wife the news and, expectedly, the aide-de-camp seduces Eugeine (no one is really sure why) and Clisson decides to die. After bitterly and passive-agressively demanding that Eugenie "live contentedly without ever thinking of the unhappy Clisson" and that his sons "may not have the ardent soul of their father, lest they be victims of men, of glory and of love". Clisson then gets "pierced by a thousand blows" (ouch) and dies. The End.

Whatever your personal feelings on Napoleon's epic military career, I think we can all agree that it's good thing that his literary career came to an end.

Friday, June 19, 2009

Erickson's "historical entertainment": Neither Historical Nor Entertaining

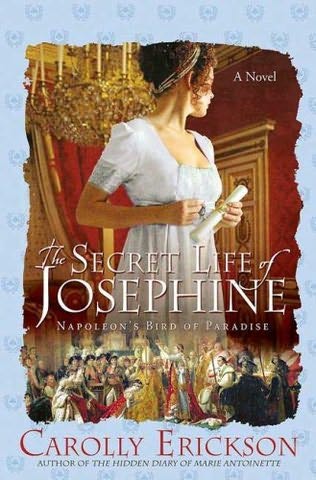

The Amateur Historian picked up a novel entitled The Secret Life of Josephine: Napoleon's Bird of Paradise from her local library, which was just the beginning of her intellectual torture.

The Amateur Historian picked up a novel entitled The Secret Life of Josephine: Napoleon's Bird of Paradise from her local library, which was just the beginning of her intellectual torture."Hunh," said the Amateur Historian to herself. "The author seems familiar. Maybe I've liked her previous stuff? I'll check it out."

Unfortunately, the Amateur Historian was familiar with the author because she wrote, without doubt, the worst book I have ever read, the godawful excuse for a novel, The Hidden Diary of Marie Antoinette, which, upon reflection, deserves every nasty thing the Amateur Historian is insinutating.

Truth is, according to Kierkegaard, subjective, so someone may find redeeming features in The Hidden Diary of Marie Antoinette. The Amateur Historian does not. Erickson prides herself on writing something called, "historical entertainment", which is neither historical nor entertaining. In these sad excuses for works of even dubious literary merit, Carolly Erickson picks a famous female historical figure, preferably one with a crown, and invents a really boring and simplistic world in which a simplified-to-the-point-of-inanity version of said historical figure makes the readers wish for the protagonist's painful demise with every page.

The Amateur Historian is a huge fan of the Empress Josephine and has read some marvelous historical fantasies about Josephine wherein the author actually does research, effectively simplifies the historical event to narrative form while keeping most of its complexity and presents a sympathetic but flawed character whose motives are understandable and who seems a genuine part of their society. Those books were the Josephine B trilogy by the marvelous Sandra Gulland.

It was not this wretched excuse for fiction by Erickson, which ought to have been named Josephine's Dear Penthouse Letter: A Bizarre Metaphor That Does Not Even Appear in the Text.

This book, though I hesitate to call it a book since it failed so much at being part of any genre but that of Gross Stupidity, has little to no relationship with historical fact, except that it appears Erickson once-upon-a-time read a general life-and-times biography of Josephine and decided that the characters were too complex and the time period too interesting and, furthermore, that the mentions of Josephine's love affairs weren't explicit and annoying enough.

Thus, this travesty of a novel was vomited forth into hardback.

I cannot begin to say how truly awful this book was. I hated it. I hated every historical inaccuracy, I hated every character Erickson introduced and I hated the fact that an intelligent, politically astute, clever woman was reduced to Miss Look-Who-I-Slept-With (which is apparently most of Europe). There was so much more to Josephine than the fact that she had sex! Unfortunately, Erickson either doesn't believe so, or feels that a complex emotional, spiritual and/or intellectual inner life makes for boring reading. Ditto with historical fact. Who cares how Napoleon's Grande Armee, the largest military force Europe had ever seen, met with disaster in Russia if there isn't sex involved?

And then, there is her godawful Napoleon. This is a man who is still revered as a hero, who inspired the poorest, worst-supplied army in Europe to capture Italy from the supposedly unbeatable Austrian forces, who created an entire legal system, who seized control of France when he was only thirty and whose army was so devoted they turned on Louis XVIII to support Napoleon at Waterloo. You'd be surprised by that if your only knowledge of the Napoleonic era came from this awful excuse for historical fiction. Napoleon is truly hateful and amazingly stupid. Though he hates Josephine (this from a man who, according to his generals, worshiped his wife, and whose existing letters to her are embarrassingly explicit) and grows to loathe her over the course of the novel, he bows to her every whim. God alone knows why, since this Josephine was one of the most unappealing characters I've had the misfortune to read. She is flat, one-dimensional, boring, and so annoying I still had no sympathy for her aafter the author attempted to force the readers to like Josephine by having someone rape the future Empress (which is just one of many "what the hell?" moments for anyone with a passing acquaintance with the historical time period or personnages).

I would like to give this novel a negative grade for not only failing to be even accidentally historically accurate, but also failing to have any of the conventional traits of fiction, like, well-rounded, interesting characters, a compelling plot, useful dialogue, wit, intelligence or proof of the author's basic literacy. What was the point of writing a prologue displaying that she had, in fact, done research, when absolutely none of it made it into the book?

Thus, this travesty of a novel was vomited forth into hardback.

I cannot begin to say how truly awful this book was. I hated it. I hated every historical inaccuracy, I hated every character Erickson introduced and I hated the fact that an intelligent, politically astute, clever woman was reduced to Miss Look-Who-I-Slept-With (which is apparently most of Europe). There was so much more to Josephine than the fact that she had sex! Unfortunately, Erickson either doesn't believe so, or feels that a complex emotional, spiritual and/or intellectual inner life makes for boring reading. Ditto with historical fact. Who cares how Napoleon's Grande Armee, the largest military force Europe had ever seen, met with disaster in Russia if there isn't sex involved?

And then, there is her godawful Napoleon. This is a man who is still revered as a hero, who inspired the poorest, worst-supplied army in Europe to capture Italy from the supposedly unbeatable Austrian forces, who created an entire legal system, who seized control of France when he was only thirty and whose army was so devoted they turned on Louis XVIII to support Napoleon at Waterloo. You'd be surprised by that if your only knowledge of the Napoleonic era came from this awful excuse for historical fiction. Napoleon is truly hateful and amazingly stupid. Though he hates Josephine (this from a man who, according to his generals, worshiped his wife, and whose existing letters to her are embarrassingly explicit) and grows to loathe her over the course of the novel, he bows to her every whim. God alone knows why, since this Josephine was one of the most unappealing characters I've had the misfortune to read. She is flat, one-dimensional, boring, and so annoying I still had no sympathy for her aafter the author attempted to force the readers to like Josephine by having someone rape the future Empress (which is just one of many "what the hell?" moments for anyone with a passing acquaintance with the historical time period or personnages).

I would like to give this novel a negative grade for not only failing to be even accidentally historically accurate, but also failing to have any of the conventional traits of fiction, like, well-rounded, interesting characters, a compelling plot, useful dialogue, wit, intelligence or proof of the author's basic literacy. What was the point of writing a prologue displaying that she had, in fact, done research, when absolutely none of it made it into the book?

There is nothing redeeming about this novel. If you can find it, Gentle Readers, pray inform me. I gave up when Josephine decided to travel to Russia after Napoleon.

... on second thought, that would mean forcing my Gentle Readers to expose themselves to such radioactive garbage. Forget the existance of this book. It will be better for everyone involved. I am personally attempting to find brain bleach to forget I ever wasted my time on something so hopelessly bad.

Sunday, May 3, 2009

Another Bad Choice in Publishing from the Shelley Family

Comparatively recently (as in the 1950s), scholars found an unpublished novella by Mary Godwin Shelley, author of the generally grossly misinterpreted novel Frankenstein. This novel was in a similar Gothic vien and is called Mathilda.

It is... strange, to say the least. Like many early novels, Mathilda is semi-autobiographical. Mary Shelley's mother, the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, died shortly after Mary Shelley's birth; Mathilda's mother does as well. Mary Shelley grew up in comparative seculsion in Scotland; so does Mathilda. When Mary Shelley's father, William Godwin, fetched her from Scotland to bring her to London, he remarked on the remarkable similiaries in face and form between Mary Shelley and her mother.

However, Mathilda's father returns for his daughter (Mathilda's father, who never gets a name, has been wandering around Europe for no easily discernable reason other than narrative convenience), remarks several times on her similarities to her mother, and sweeps her off to London where he promptly falls in love with her.

... yes, you read that correctly, gentle reader. Mathilda is, in fact, about incest. Incest was a popular subject with the second generation English Romantics. Byron's heroes, when not homoerotically tangled in a "last embrace of foes" that exceeds in passion any between a man and a woman (read The Giacour for more details), tend to be in love with someone morally and ethically unsuitable. This someone often turns out to be the hero's sister.

Mary Shelley sent this manuscript to her father, William Godwin, a successful publisher. The Amateur Historian assumes that Mary Shelley had thought that the novel would sell as well as Frankenstein had, considering that it was both extremely creepy and tragic and concerned a popular trope, i.e. incest. Her father was a well-known publisher; surely he would be able to print it?

Wisely, William Godwin decided not to publish it, lest London society thought him in love with his daughter.

Wednesday, January 7, 2009

Georgette Heyer's "Friday's Child"

Gentle Readers, the Amateur Historian will, on occasion, review a work that has some affiliation to the Period Mentioned in the Header. Generally these works will have at least something to do with the absurdity of history, though whether or not the author intended it is a matter of debate.

Friday's Child, by Georgette Heyer, takes place in the Regency Period (1811-1820, when George III went permanently mad and his much-hated son George IV took over), where real men wore heeled boots and lavender kid gloves. I'm not entirely sure if the title Friday's Child refers to the old nursery rhyme which informs one that though Saturday's child works hard for a living, Friday's child is loving and giving, or to Man Friday, Robinson Crusoe's justification for colonization... er, devoted companion.

In either case, it is certain it refers to Hero Wantage, the Heyeroine, if you will, who has the decision-making capabilities of a stunned lemming in the last stages of a degenerative brain disease. This then makes the Heyero, the viscount Sheringham known as “Sherry” and also known as someone so impulsive it makes him look as if he has some kind of learning disability, the Robinson Crusoe figure, who must show this strange, uncivilized Companion (Hero has lived in the country her entire life) the Ways of the World. In this he is helped by his three absolutely hilarious friends: Gil, who appears to be the only sane and practical person under the age of thirty in Regency England and is totally gay for Ferdy, Ferdy, who excellently shows the dangers of Your Brain on Dangerous Amounts of Inbreeding, and George, Lord Wrotham, who is the most splendid send-off of a Byronic Hero that this Amateur Historian has ever seen.

It all begins when Sherry, in some financial difficulties, decides to propose to the heiress Isabella, who wisely tells him to bugger off, the dissolute bum he is. Sherry gets scolded by his mother and uncle for being immature and failing to marry Isabella causing Sherry to come up with the brilliant plan to marry the first woman he sees. Yeah, that’ll show ‘em you’re an adult now.

Enter Hero, who lives next door. She’s been secretly in love with Sherry for years and agrees to elope with him at once. After Sherry realizes the practical difficulties of marriage (where does he get a marriage license? Does he have to have a ring? Ought he to see a lawyer? Where the hell is the church?), he and Hero marry. Hero promptly gets into buckets of trouble because her only guide in how to act in society is Sherry, who, being a somewhat dissolute bachelor who has the impulse control of a spastic two-year-old, sets her an extremely bad example. The rest of the book is devoted to the hilariously tormented love affair between the practical-minded Isabella and George, who mopes about romantically, threatens suicide or homicide just for fun and keeps trying to challenge people to duels, and the increasingly bad situations from which Sherry, Gil, Ferdy and George have to save Hero. “She’s as innocent as a Kitten,” quoth Sherry. “She doesn’t know any better!”

However, he doesn’t manage to tell Hero he doesn’t blame her for being an incredibly twee little idiot and so she runs off to Gil for help when Sherry of the notoriously absent self-control pitches a fit when she manages to nearly ruin her reputation. Gil (with the help of Ferdy and George) comes up with a plan to get Sherry to fall in love with Hero. Hilarity Ensues.

This is where Heyer really excels. She creates these absurd, whacky Wodehousian plots that come together very neatly and very satisfyingly in the final chapter. The best part is that they seem totally justified based on her characters. This is possibly why the plot of Friday’s Child is so absolutely hilarious: all the characters are so stupid that they get into one of the absurdest and yet most believable denouements I have ever read. (Just to pique your curiosity, Ferdie gets terrified by Greek mythology and wakes Sherry up at two in the morning, Gil jaunts off to Bath, Hero takes an asthmatic pug with her in a romantic kidnapping, Isabella totally shuts down a would-be seducer, George nearly shoots someone in an inn, and Sherry jumps out of a moving carriage to try and kill George.)

Heyer is famous for perfectly capturing Regency society, with all its furbelows and frivolities. Her books are an amazingly accurate portrait of the life of high society (the ton) of Regency England. People take boxing lessons with Gentleman Jackson, make outrageous drunken bets, lose fortunes at the card tables, and race carriages everywhere. I’m not sure of the amount of useless twits in Friday’s Child is an accurate representation of Regency society, but considering that everyone in England looked to a man famous for spending four hours getting dressed every morning to tell them what was fashionable and how they ought to act, it might be possible.

Friday's Child, by Georgette Heyer, takes place in the Regency Period (1811-1820, when George III went permanently mad and his much-hated son George IV took over), where real men wore heeled boots and lavender kid gloves. I'm not entirely sure if the title Friday's Child refers to the old nursery rhyme which informs one that though Saturday's child works hard for a living, Friday's child is loving and giving, or to Man Friday, Robinson Crusoe's justification for colonization... er, devoted companion.

In either case, it is certain it refers to Hero Wantage, the Heyeroine, if you will, who has the decision-making capabilities of a stunned lemming in the last stages of a degenerative brain disease. This then makes the Heyero, the viscount Sheringham known as “Sherry” and also known as someone so impulsive it makes him look as if he has some kind of learning disability, the Robinson Crusoe figure, who must show this strange, uncivilized Companion (Hero has lived in the country her entire life) the Ways of the World. In this he is helped by his three absolutely hilarious friends: Gil, who appears to be the only sane and practical person under the age of thirty in Regency England and is totally gay for Ferdy, Ferdy, who excellently shows the dangers of Your Brain on Dangerous Amounts of Inbreeding, and George, Lord Wrotham, who is the most splendid send-off of a Byronic Hero that this Amateur Historian has ever seen.

It all begins when Sherry, in some financial difficulties, decides to propose to the heiress Isabella, who wisely tells him to bugger off, the dissolute bum he is. Sherry gets scolded by his mother and uncle for being immature and failing to marry Isabella causing Sherry to come up with the brilliant plan to marry the first woman he sees. Yeah, that’ll show ‘em you’re an adult now.

Enter Hero, who lives next door. She’s been secretly in love with Sherry for years and agrees to elope with him at once. After Sherry realizes the practical difficulties of marriage (where does he get a marriage license? Does he have to have a ring? Ought he to see a lawyer? Where the hell is the church?), he and Hero marry. Hero promptly gets into buckets of trouble because her only guide in how to act in society is Sherry, who, being a somewhat dissolute bachelor who has the impulse control of a spastic two-year-old, sets her an extremely bad example. The rest of the book is devoted to the hilariously tormented love affair between the practical-minded Isabella and George, who mopes about romantically, threatens suicide or homicide just for fun and keeps trying to challenge people to duels, and the increasingly bad situations from which Sherry, Gil, Ferdy and George have to save Hero. “She’s as innocent as a Kitten,” quoth Sherry. “She doesn’t know any better!”

However, he doesn’t manage to tell Hero he doesn’t blame her for being an incredibly twee little idiot and so she runs off to Gil for help when Sherry of the notoriously absent self-control pitches a fit when she manages to nearly ruin her reputation. Gil (with the help of Ferdy and George) comes up with a plan to get Sherry to fall in love with Hero. Hilarity Ensues.

This is where Heyer really excels. She creates these absurd, whacky Wodehousian plots that come together very neatly and very satisfyingly in the final chapter. The best part is that they seem totally justified based on her characters. This is possibly why the plot of Friday’s Child is so absolutely hilarious: all the characters are so stupid that they get into one of the absurdest and yet most believable denouements I have ever read. (Just to pique your curiosity, Ferdie gets terrified by Greek mythology and wakes Sherry up at two in the morning, Gil jaunts off to Bath, Hero takes an asthmatic pug with her in a romantic kidnapping, Isabella totally shuts down a would-be seducer, George nearly shoots someone in an inn, and Sherry jumps out of a moving carriage to try and kill George.)

Heyer is famous for perfectly capturing Regency society, with all its furbelows and frivolities. Her books are an amazingly accurate portrait of the life of high society (the ton) of Regency England. People take boxing lessons with Gentleman Jackson, make outrageous drunken bets, lose fortunes at the card tables, and race carriages everywhere. I’m not sure of the amount of useless twits in Friday’s Child is an accurate representation of Regency society, but considering that everyone in England looked to a man famous for spending four hours getting dressed every morning to tell them what was fashionable and how they ought to act, it might be possible.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)